HISTORY OF THE EASTERN SIDE OF ARMENIA. AGHVANK, GARDMAN, UTIK

9 Հունվարի, 2023

(BOOK SUMMARY)

The territory between the lower streams of the Araks and Kur rivers (Gardman, Utik, Artsakh, Paytakaran), is known in Armenian history under the names “the eastern side of Armenia”, “the eastern world”, and “world of Aghvank”.

The area between the Sevan and Mrav watershed mountain ranges and the Kur River of the same territory, was known as Gardman in Armenian historiography in the early Middle Ages. Gardman is also known under the names Utik, Shakashen (Shikashen), and Arshakashen. In the Ashkharatsuyts (“World Map”, early VII century), the twelvth province of Greater Hayk is called Utik, which consists of eight districts: Aran-rot, Tri (Tre), Rot-Parsean, Aghoue, Tus-Kustak, Gardman, Shakashen, and Uti Arandzak (Ut-Rostak). Due to administrative changes, the number of provinces increased to nine, after the addition of Tavush. As we can see, the names Gardman, Utik, and Shakashen (Shikashen) used for the provinces, are also names of districts. According to the position occupied by the rulers of the district, in the given period the province was named after the district: Gardman, Utik, Shakashen (Shikashen). Thus, all three names carry equal weight.

New studies being carried out allow us to assert that the world of Armenian Aghvan included not only the West Kur, but also the plain of the Left Bank Kur, to the southern branches and gorges of the Caucasus Mountains, to the places of residence of the Caucasian tribes living there, as evidenced by Greek, Roman and Armenian historians (this issue is discussed in detail in the paper).

Let us focus on the names of Aghvank, Gardman, Utik, and Shakashen. The name Gardman consists of the components gard (weapon)- and -man (human), and it is believed to bear the meaning “people (land) of arms”. The name Uti (Utik), according to popular opinion, comes from the name Etiuni (land, tribe) mentioned in Araratian (Urartian) cuneiform inscriptions (Nikolsky M.V., Cuneiform Inscriptions of Transcaucasia, MAK, V, p. 92). According to one of the new views put forward, the name Shikashen (Shakashen) is derived from the root Shek-.

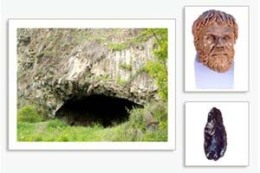

At the end of the 19th century and start of the 20th century, archaeological excavations in Gardman yielded amazing artifacts including bronze items, weaponry, jewelry, beautifully decorated clay vessels, and more. The clay vessels are exceptionally lovely, designed with geometric shapes (crosses, swastikas, circles), plants (Tree of Life), animals (goats, bucks, deer, horses, dogs, snakes),

328 The work History of the Eastern Side of Armenia (Aghvank, Gardman, Utik), was published in 2015. The “Summary” of the book is presented. and images of people. Depicted on many of the recovered items is the Sun-God’s symbol, the swastika (arevakhach, “sun-cross”). Unfortunately, many of the traces of the findings have been lost (Meshchaninov, I. Transcaucasian Hieroglyphic Messages, GAMK, 1932, 34, p. 55). The majority of them were sent to St. Petersburg, Moscow, and Tibilisi; a particularly large number of items were sent to the Caucasian Museum in Tbilisi (Collection of the Caucasian Museum, vol. VI, p. 123-125; S. Karapetyan, “Armenian Collection of the Caucasian Museum”, Yerevan. 2004).

Since the mid-20th century, the Soviet, mainly Azeri, specialists have been conducting new archaeological excavations in the Gardman area (Kandak-Mingechaur, Gandzak, Khanlar, Shamkhor, Ghazakh, Hartshangist [Chovdar], Khachi Aghbiur [Khachbulag]). The findings of the excavations, which date to the III-I millennia B.C., were taken to Baku and stored in museums there (Guide to the Exhibitions of the Azerbaijan History Museum, Baku, 1958). Today, these items are the main cultural values on the basis of which the Azeris are trying to create a history for themselves.

The Armenian Highlands and the surrounding areas, including Gardman, are an important center of Eneolithic (Copper Age, V-IV millennia B.C.) culture. Well studied Eneolithic sites in the Ararat Valley include Khatunarch, Mokhrablur (Ejmiadzin), and Teghut, and forming the continuation of the Ararat Valley are the sites of Ghazakh, Shomu Tepe, Toyre Tepe, Gargalar Tepe, Baba-Dervish, and other settlements of the Aghstev River valley. The sanders, mortars and crushers found in the Turkish-named settlements of the Aghstev River valley, allow us to conclude that the inhabitants were mainly engaged in agriculture, growing grain plants. The discovery of an abundance of cattle bones, belonging to small and large bovines, testify that the inhabitants also practiced animal husbandry.

Gardman is one of the most well known centers of the Kura-Araxes culture (IV-II millennia B.C.). The first archaeological materials of this culture were discovered in 1869 near the village of Zaglik (Gandzak region), and in 1879 in Armavir (Armavir region). The recovered materials were initially studied and described by B. A. Kuftin, conditionally calling it the Kura-Araxes culture (Kuftin B. A., Urartian “Columbarium” at the foot of Ararat and Kuro-Araks Neolithic, “Bulletin of the State Museum of Georgia”, 1943, v. 13 V). One of the oldest settlements in the Armenian Highlands, and in the world of Gardman, is Mingechaur (Kandak) in the Armenian province of Aghberd (now Aghdash), where archaeological excavations have discovered remarkable cultural values representing the culture of the Kura-Araxes (III-II millennia B.C.). In the excavations conducted between 1946-1950, more than 14,000 archaeological objects were unearthed, which were spread out over an area of 35,000m2. The example of one tomb is enough to confirm just how rich they are in cultural valuables. For example, an entire large showcase-cabinet in the Museum of History of Azerbaijan displays multiple items found in the tomb of just one nobleman (Exhibition guide…, 1958). Special attention should be paid to the animal-shaped, bird-shaped, mixed hybrid and other shaped clay vessels, as well as the elongated shoe-shaped vessels and rhytons, which actually had ritual significance. Excavations in 1948 were important in determining the ethnicity and Christianity of the ancient and medieval inhabitants of Kandak-Mingechaur. During the excavations, a church temple, buildings, pillar anchors, remains of windows and doors, and other architectural details were found, on which the letters of the Armenian alphabet are clearly visible. There are also writings which are considered Albanian. Bronze and iron crosses were also discovered, remains of incense sticks, and so on.

The Kura-Araxes culture was followed by the Middle Bronze Age (21st-19th centuries B.C.), cultures of the Late Bronze and Iron Ages (18th-7th centuries B.C.). Archaeological excavations indicate that Gardman was included in the cultural area of the Armenian Highlands, and the culture created in this territory is closely related to the culture created in other parts of the Armenian Highlands.

The Kura-Araxes culture, and all other cultures, are cultures defined by agricultural, sedentary tribes, which is characteristic of the natives of the Armenian Highlands, the Hay-Armens. Another agricultural and sedentary culture is the Yaloilutepe culture (Kapaghak, now the vicinity of Gabala, Kutkashen) of the Kur Left Bank, which is dated to the 3rd-1st centuries B.C..

Since ancient times, all the Armenian states have tried to unite the Armenian tribes and state formations living in the territories from the Mediterranean Sea to the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. Inscriptions of the kings of the ancient Armenian state of Ararat-Urartu (9th-7th centuries B.C.) Ishpuini, Argishti I, Sarduri II, and others, testify that as a result of their campaigns to unite the Armenian Highlands, Gardman and Artsakh became part of the Armenian state of Ararat-Urartu.

Greek and Roman historians (Strabo, Polybius, Pliny the Elder, Plutarch, Pliny) provide information about the Albanian and Caucasian mountain tribes in the period up to the end of the I millennium B.C., from sources consulting older written sources (lost records of biographers and companions of the Seleucid commander Patrocles, Roman commanders Lucullus, Pompey and Antony).

They mention the tribes of Alban, Udini, Utidorsi, Uiti, Lbin (Lpni), Silvii or Silver (Chighb), Didur (Didoy), Sod, Gel, Lek (Leg), and others living in the coastal areas of the Caspian Sea and the mountainous areas of the Samur River, to the Caucasus Mountains and the land of Iberia. In Armenian written sources, Movses Khorenatsi (5th century), Yeghishe, Pavstos Buzand (5th century), Ashkharhatsuyts (7th century), and Movses Kaghankatvatsi (7th century), the same tribal territories are mentioned under the names Maskut, Aghuatakan (Akhti), Ghek (Tsakhur), Tavaspar (Tabasarantsi), Lek (Lezgi), Gar Gar, Khundz, Hejmatan, Lpni (Lahichner), Didoy, Chighb, and others. We notice the tribes they mention are Caucasian tribes, living to the north of the branches of the Caucasian mountain ranges and the coastal areas of the Caspian Sea.

In the works of Greek and Roman historians, and on the basis of their information on ancient maps of the world, (Strabo, 1st century B.C. to A.D. 1st century, Geography, XI, chapters III, 2, 14 [4]; Ptolemy, 2nd century, Geography, VI, XI, 3) Gardman-Utik is always marked within the borders of Armenia, and the Kur River is considered the natural border of Armenia. The Kur River is attested to as the natural border of Greater Hayk according to Ashkharatsuyts. However, the Greek historians (Strabo) and the Armenian Ashkharatsuyts, testify to the Armenian provinces on the Left Bank Kur River. Strabo mentions the Armenian provinces of Khorzene (Kgharjk) and Cambysene (Komissene, Kambejan) (Strabo, Geography, XI, chapter III, 2, 14/4). The province of Anahtakan Yerkir is mentioned by Flavius Josephus (1st century, it has reached us through Cassius Dio; Cassius Dio, History of Rome, book XXXVI, 5).

The provinces of Aghberd (also Kaghadasht, Kaladzor, later Aghdash), Dasht-i-Bazkan (Hejeri, now Ujari, located in the Shirvan steppe), Kapaghak (also Vostan-i-marzpan, now Kabala) and others are mentioned in the Ashkharatsuyts. Ancient written sources allow us to assert that the area from the Left Bank Kur to the foot of the Caucasus Mountains, was populated by Armenians and was a constituent part of the Armenian region of Aghvank.

The historian Movses Khorenatsi (5th century) reports important evidence about the origin of the name Aghvank, and about the boundaries of the land of Aghvank. He writes that the Sisak clan, native to Hayk, inherited the plain of Aghvan and the mountain adjacent to the plain (at the foot of the Caucasus Mountains). Then, the Armenian king Vagharshak appointed Aran, the son of Sisak, as a prefect in the eastern-northern region of Armenia, along the course of the great river called Kur, which passes through a large plain. Writing about the origin of the name Aghvank, Khorenatsi states that the world (the region) was called Aghvank, after (Sisak’s) sweet (=aghu) character, because he was nicknamed “aghu” (sweet, pleasant). The children of the descendants of Aran ruled Utik, Gardman, and Tsavdek (Artsakh) (M. Khorenatsi, History of Armenia, 1981, pp. 127, 129).

Gardman-Utik was part of the Armenian state during the Ararat-Urartian Aramian dynasty (9th-6th centuries B.C.), as well as the Yervanduni (6th-2nd centuries B.C.), Artashesian (2nd century B.C. — A.D. 1st century), Arshakuni (A.D. 1st-4th centuries), Bagratuni (A.D. 9th-11th centuries) and Zakaryan (A.D. 12th-13th centuries) dynasties. However, Gardman-Utik was often separated from Hayk and absorbed into foreign states. The first treaty that separated Gardman from Hayk was signed between Rome and Persia in 363. In 371, during the reign of the Pope King, Gardman reunited with Hayk.

The first division of Armenia between Rome and Persia took place in the year 387. Gardman, along with the other peripheral provinces, was again separated from Hayk and integrated with Persia. In the mid-5th century, Gardman and Artsakh were incorporated into the newly established province of Aghvank. Following this administrative change, the church of that district was separated and was called the Catholicosate of Aghvan, remaining subordinate to the Armenian Church of the Enlightenment.

In 7th century Armenia (let us note that following the first division of Hayk, Armenian chroniclers began using the name Hayastan), Aghvank (and Gardman) was subordinate to Arabic rule, and was included in the governorship of Armina (Armenia). The Arabs pursued a policy of converting the peoples they conquered to Islam. Subjects that converted to Islam were exempted from taxes, received benefits, were appointed to various positions, and so on. As a result of this policy, many tribes, including Caucasian tribes, adopted Islam. The Armenian subjects, thanks to their strong culture, language, writing, religion and traditions, were able to preserve their ethnic identity.

In the year 885, Armenian statehood was restored. The weakening Arab caliphate recognized Armenia’s independence. Ashot Bagratuni (Ashot I, 885-890) was proclaimed king of Armenia. Showing great stately, diplomatic, and military skill, Ashot I Bagratuni was able to unite many Armenian principalities in the restored Armenian state, including Artsakh and Gardman. At the end of the 9th century, the border of Bagratuni Armenia reached to the Kur River in the northeast. However, the Bagratunis did not succeed in uniting Armenia into one single state. As a result of the short-sighted policy of Byzantium in 1045, the Kingdom of Bagratunian Ani was destroyed. Deprived of military might, Armenia found itself in an unprotected position. This short-sighted policy of Byzantium was fatal for both Armenia and Byzantium itself. In 1047, Armenia was invaded by new, very dangerous enemies, the Seljuk Turks, who defeated the Byzantines near Manazkert in 1071. A defenseless Armenia (also Gardman), followed by Byzantium, was conquered by the Seljuk Turks. Relatively free from the Seljuk invasions, Georgia was able to conduct successful military operations under the leadership of the Armenian commanders Zakare and Ivane Zakaryan. In 1196, Zakare and Ivane defeated the army of Amir in Gandzak. Gardman, along with other Armenian territories, were passed to the Zakaryans. However, new enemies continued to appear. The Seljuk Turks (11th century) were followed by the Mongol Tatars (13th century); then, the hordes of Timur Lenk (14th century) appeared. On the eve of the Mongol Tatar invasions, the demographic picture in Transcaucasia changed dramatically. In Atropatene, the Turkic-speaking element became dominant. The populations of the territories to the north of the Left Bank Kur River gradually became Turkified. Turkish, Tatar, and Kurdish tribes settled in the fertile plains and valleys of the Armenian Highlands (Gardman, Nakhijevan). The indigenous Armenian population of Gardman and Nakhijevan was forcibly resettled during the reign of Timur Lenk’s son, Miran Shah (1396). Under these conditions, the Armenian rural communities of the foothill and mountain regions proved to be viable, preserving their traditional settlements, principles, and customs.

From 1512 until 1639, in short intervals, Armenia became a military theatre during the wars between Ottoman Turkey and Safavid Iran. Armenian localities and provinces were subjected to the forces of the shah or sultan. A treaty signed in 1639 gave Persia total control over the historical Armenian states of Syunik, Artsakh, Gardman, Paytakaran, and Parskahayk, as well as the eastern parts of the states of Ayrarat, Gugark, and Vaspurakan. The mountaineers of the Caucasus, especially the Lezgis, continued their plundering attacks. They forced thousands of Armenians into captivity, predominantly women and children. This is the reason that modern populations of people dwelling in the Caucasus, especially the Lezgis and Avars, contain such a large number of phenotypically Armenian people (representatives of the Armenoid anthropological type). Gardman Armenians also appeared in Georgia for various reasons (captivity, famine, epidemics, emigration). As a result, in Kakheti, Tiflis (Havlabar), and other settlements of Georgia, the Armenian population was constantly increasing, in particular the number of Gardman Armenians.

Having been physically separated from Armenia, Gardman was able to keep its ties to Mother Armenia through spiritual and cultural means. Within the community of Gardman Armenians, widespread oral stories, traditions, legends, songs, dances, ritual ceremonies, and other elements testify that a spiritual connection has always existed between Gardman and the other Armenian lands. Gardman khachkars (cross-stones) and the art of rug making are subjects of a separate study. Gardman khachkars are especially beautiful, decorated with delicate plant patterns, images of animals, and human figures. Unfortunately, the majority of them have been destroyed. Today, Azeris are trying to appropriate the Armenian khachkars, claiming they are Albanian. The same beautiful, elegant images of plants and animals, as well as human forms, are depicted on Gardman carpets. It should be noted, most of the khachkars have been destroyed and, like other Armenian monuments, our carpets now decorate the museums of Azerbaijan.

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, with far-reaching goals in mind, Azeris bought handmade Armenian carpets from Armenian villagers, or exchanged those carpets with factory manufactured carpets. Carpets, as well as other culturally valuable materials created by the Gardman Armenians, appear in the museums of Azerbaijan as archaeological finds. A carpet museum was created in Baku, and carpet making was declared an important branch of culture created by the Azeri people. An Armenian carpet, like a khachkar, was created for a specific reason, and inscriptions were made on the carpets documenting such information (names, years). Azeris have found ways to remove Armenian inscriptions from carpets. They cut off and remove this part of the carpet, then claim that these are normal signs of wear. Additionally, in the collections of carpets called Azeri, there are a large number of carpets representing not only the settlements of West Kur, but also the settlements of Shamakh, Nukh (now Shaki), and other settlements of the Left Bank Kur River, which are considered to be the original settlements of Armenians. In the 16th-17th centuries in Shirvan, there were about 60 Armenian villages. The European traveler Adam Olearius (17th century) attests to this fact (Leo, n. 3, 1969, p. 169). The Armenian inhabitants of these settlements were Islamized between the 18th and 19th centuries, or regularly massacred (the most recent was the massacre of the Armenian residents of Nukhi and Shamakhi in 1918).

At the start of the 19th century, with the active participation of Armenians, Russians settled in Transcaucasia. The Russo-Persian war occurred between 1804-1813. In 1813, according to the treaty concluded in Gulistan, the Karabakh and Gandzak khanates were transferred to Russia, along with Georgia, historical Aghvank (Albania), and other Armenian territories. After the khanate of Gandzak (Ganja) came under Russian occupation, it was renamed the province of Elizavetpol. In 1828, after Eastern Armenia came under Russian occupation, the Armenian population migrated from Persia, Western Armenia, and elsewhere to the Ararat Valley, Artsakh, Gardman, and Javakhk. The immigrants mostly settled in the former abandoned Armenian settlements, where traces of Armenian buildings (monasteries, churches, khachkars, graves with Armenian inscriptions) have been preserved. Completely disregarding the existence of ancient Armenian monuments in those settlements (some dating to the 5th-7th centuries), Azeri (and Georgian) historians falsely claim that Armenians were not in these territories until after 1828.

Armenians had high hopes that the Russians, their brothers in the Christian faith, would put an end to the interethnic conflicts which had caused great suffering for the Armenians. However, the Russian tsars were not interested in the security of the peoples living within their empire, even the Christians, or the well-being of the Armenians. As other foreign rulers had done, the Russian tsars pursued a policy of expelling Armenians from Armenia. The Armenians were encouraged to migrate to the occupied territories near the Caspian in the North Caucasus, and Russian (also German) immigrants settled in Gardman and other native Armenian areas. Everything was done (new administrative divisions, emigration) to ensure that the Armenians did not form a majority in their homeland. Subsequent events showed that between 1905-1906, with the connivance of the Russian government, Armenian-Turkish (Tatar) clashes began in Transcaucasia (allegedly at the instigation of international secret organizations).

At the end of the 19th century, Bishop Makar Barkhudaryants reports interesting information about the multilingual tribes living in Gardman, Artsakh, and the areas north of the Kur River, up to South Dagestan and Absheron. In 1890, he was present in those areas, where he wrote down what he saw and heard, and published them in a valuable work (Makar Barkhudaryants, History of Aghvan, n. 1, Vagharshapat, 1902, n. 2, Tiflis, 1907) which plays a very important role in the study of the history of Aghvank (Gardman-Utik, Artsakh). As if it were an established fact, the author painfully attests to many Armenian villages that were forcibly converted to Islam and became Turkish-speaking. Barkhudaryants was writing around 1711-1722 about the Muslimization of the Armenian population of Shaki province, which was carried out by force. He writes about Vantam (“ijevan tal”, to give lodging), Kutkashen (“khuti vra shinvats”, built on a ledge), Zardun, Bum, Khachmas (“khachi masunk”, relic of the cross), Patar, Vardanlu (“Vardani gyugh”, Vardan’s village), Ermanit (“Hayi gyugh”, Armenian village), Mukhants (“mukhn antsats”, the smoke passed), Oraban (“orva khosk/gorts”, daily word/work), Kungivt (“kuneh gtnogh”, finder of sleep), Ptez (“partez”, garden), Zayzit, Kish (Gis), Kokhmukh (“mukheh kokhel votkov”, stomp out the smoke), Malgh (“malukh”, rope) and other settlements, whose inhabitants were Islamized. Let us add a few more: Balakhani, Bibi Eybat, Aresh, Khanabad, Kendek, Gavarli… The Muslimized Armenians retained their Armenian names and traditions for a long time. They continued to kiss the khachkars, frequent pilgrimage sites, light candles during prayer, make the sign of the cross over their sleeping children, knead dough with the meal taken from the fire, etc. The most striking difference between them and the Turk-Tatars are the external features. Muslimized Armenians have typical Armenian phenotypes, adhering to the Europoid race’s Armenoid anthropological type (round, short skull with a flat backing, high nasal bone, large eyes, wavy hair, light skin), in contrast to the Turk-Tatar, which are classified as a Mongoloid anthropological type (long head, protruding cheekbones, dark and slanted eyes, low nasal root, developed fold of the upper eyelid [epicanthus], dark skin often with yellow undertones). As the inhabitants of the settlements were Muslimized, the names of the settlements began to change. For example, Vardanakert became Javad, Paytakaran became Salyani, Yevtnaporakian Bagin became Surakhani, Alevan became Avsharan, Aghberd became Aghdash, and Bagu became Baku (Bag=Bog, cf. Bagavan, Bagnayr, Bagayarich).

At the end of the 19th century, the territories south of the Kur River, Gardman and Artsakh, continued to be predominantly populated by Armenians. M. Barkhudaryants offers some interesting information about the largely and partially Armenian-populated Artsakh and Gardman provinces, including Gandzak, Yelenendorf (Khanlar), Shamkor, Ghazakh, and other cities, as well as Getashen, Banants, Voskanapat, Mirzik, Brajur, Karhat, Kirants, and ten other settlements. However, many provinces were emptied of Armenian inhabitants. Most of the steppe provinces were inhabited by nomadic Muslim Arabs. Tatar tribes occupied the valleys of the Zakam River, and the newly arrived Kurdish tribes occupied the provinces of Artsakhi Tsar, Vaykunik, Harchlank, and Berdadzor. The majority of those tribes were also nomads.

The Russian tsars’ anti-Armenian policies (disallowing the Armenian-populated territories from unifying) were continued by the Bolshevik and Soviet leaders. Taking advantage of the situation created after the Russian revolutions of 1917, in May 1918 with the help of leaders of secret organizations (Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Enver, Kemal) with well-developed and far-reaching plans, a new Turkish state called Azerbaijan was created in Transcaucasia. International agent L. Trotsky had repeatedly expressed that, for the sake of the victory of the world revolution, Armenians should make concessions in favor of Turkey. He wrote about it in an openly anti-Armenian article titled “Armenia and Turkey at the Upcoming Conference”, which was published in the journal Zhizn’ Natsional’nostei on March 4, 1921.

Soviet power was established in Azerbaijan on April 28, 1920. The borders of the Soviet republics were determined arbitrarily. In some cases, the area’s ethnic population was taken into account, in other places, it was ignored. Thus, the Armenian majority populated regions of Gardman, Artsakh, and Nakhijevan became part of the newly created Turkic state called Azerbaijan. In the native homeland of other ethnic groups (Armenians, Caucasian tribes, Iranian tribes) (Left Bank Kur, Right Bank Kur: Gardman, Artsakh, Paytakaran, Nakhijevan, the southeastern part of Dagestan, the coastal regions of the southwestern part of the Caspian Sea) a state called Azerbaijan was created, whose very name did not even belong to him. The name Azerbaijan, which has been presented as a name meaning “land of fire” since the Soviet years, is a distorted form of the name Atropatene (named in honor of the Median general Atropates). The name Azerbaijan was selected by the Bolshevik leaders with a long-term scheme in mind. They wanted to export the revolution to neighboring countries, including Iran, with hopes that Iranian Azerbaijan would join the newly created Soviet Azeri state. The national composition of this state was also not homogeneous; it consisted of Muslimized Caucasian tribes (Lpin-Lahich, Lez-Lezgis, Tavaspar-Tavasparians, Gel-Gilians, Udis, Ghek-Tsakhuris), Mongol-Tatars, Seljuk Turks (Turkmen), Arabs, Iranian tribes (Talish, Tater), Armenians forcibly converted to Islam (including tens of thousands of Turkish children born to Armenian women), and from the Muslimized descendants of other tribes and peoples who appeared in that area, who were known under the general name of Tatars from the end of the 19th century. In 1926, during the All-Union Census of 1926, Transcaucasian Tatars and Turks were registered under the name “Caucasian Tatars”. After 1936, only “Caucasian Tatars” accepted the name Azeri, and they began presenting themselves with that name.

In the Soviet years, the government of Azerbaijan, with the support of Soviet scientists, in particular orientalists and historians, tried to rewrite the history of Azerbaijan in various ways, presenting it as a country with an ancient history. Anything of cultural value that was ever created on the territory of Azerbaijan was appropriated (archaeological objects, ethnographic material, folklore, prominent individuals). The Christian cultural relics (churches, monasteries, khachkars) which could not be appropriated, were attributed to Albanian tribes, whose heirs the Azeris consider themselves.

But who are the Albanians? What is their origin? What is their name? Albanian, or Aghvan? What territory did they live in? What culture did they create? What culture do modern Azeris consider “Albanian”? These are the questions that arise when studying the written sources regarding Albania (Greco-Roman sources) and Aghvank (Armenian sources). All researchers agree that it is definitely impossible to talk about a state called Albania and the people of Albania. It seems that there is a kingdom (state) named Albania or Aghvank, but there are no visible people named Alban or Agvan; there is no visible ethnic community. Meanwhile, it is directly noted that the history of Albania is closely connected with Armenia, the Armenian kings and catholicoi, the Armenian noble class, and the people. This is the reason why, not seeing an Albanian or Aghvan people, many researchers (N. Marr, G. Klaproth) identify the Albanians mentioned by Greek and Roman authors with the Alans (Marr, N., Caucasian Tribal Names and Their Local Parallels, Petrograd, 1922, Trever K., Essays…, p. 30). S. Yeremyan believes that “lbin” is the transliterated form of “alban” (Yeremyan, S., M Kalankatuysky about the embassy of the Albanian prince Varaz-Trdat…, Zap. IV. AN. USSR, vol. VII, pp. 148-149). Even K. Trever admits that it is impossible to talk about any Albanian ethnic group or ethnic community, since the “26 languages” mentioned by Strabo (Strabo does not mention the tribe, people, kingly terms) are 26 different languages, and that “they have no common language, no single tribe, no single people, no single kingdom” (Trever, K., Essays…, p. 59). Trever goes on to write, it is impossible to accurately determine either the name or the occupied territory of the union created under the leadership of the Albans, since there is very little linguistic, ethnographic, and archaeological information available (Trever, K., Essays…, p. 49). Additionally, the historian Bakikhanov, while writing the history of Azerbaijan, studied the testimonies of ancient authors, paid attention to toponyms, and tried to clarify a number of issues (Albanian tribes, their struggle against conquerors, the origin of the name Albania). Examining the historical geography and place names of Albania, Bakikhanov determined that ancient Albania was in the territories of Shirvan and Dagestan (Abas-Kuli-aga [Kudsi] Bakikhanov, Gulistan-Iram… Baku, 1926. Essays on the History of Historical Science in the USSR, vol. 1, p. 641. The work was originally written in Persian, then translated into Russian by the author. Trever, K., Essays…, p. 26).

On the basis of what facts, conclusions and consequences do some Azeris (and Dagestanis) claim that Artsakh, Gardman-Utik, and even Syunik are Albanian territories? The answer to the question is connected with the information “heard from others” by Strabo, circulated since the beginning of the 20th century, according to which, “it is said that the Armenian king Artashes I conquered lands from the surrounding nations” (Strabo, XI, 14, 5). This point of view, as well as other issues related to Albania-Aghvank, received a new development in Soviet historiography, where an attempt was made to equalize and level the histories and cultures of all the peoples of the USSR. The Armenian people, with an old, rich history and great culture, suffered the most from that policy, a part of which, Aghvank (Gardman-Utik, Artsakh, and Paytakaran), was again separated from Armenia and annexed to the Turkish state of Azerbaijan. Published works of B. Ribakov (“The Crisis of the Slave System and the Emergence of the Feudal System on the Territory of the USSR”, III-IX centuries, Moscow, 1958, Essays on the History of the USSR), K. Trever (Trever, K., Essays on the History and Culture of Caucasian Albania, IV Century B.C.. — A.D. 7th Century, M-L, 1959), V. Minorski (History of Shirvan and Derbend X-XI Centuries, Moscow, 1963), and other authors, based on the information reported by Strabo, conclude that the Right Bank Kur River (Gardman-Utik, Artsakh) was joined to Armenia during the reign of Artashes I (189-160 B.C.), after which the inhabitants allegedly became Armenian.

Let us focus on one book, K. Trevor’s famous work, Essays on the History and Culture of Caucasian Albania, IV Century B.C.. — A.D. 7th Century. This work gives answers to the questions regarding Albania. In this work, as with other cases, to put it mildly, a number of issues have been interpreted incorrectly, including the borders of ancient Armenia (during the time of Artashes I), the reasons for the creation of the Albanian kingdom, information about the state of Syunik-Sisakan, the nationality of Movses Kaghankatvatsi, and more. It should be noted, the aforementioned statements from Strabo do not mention Artsakh, Gardman-Utik, or Shakashen. In the same place, Strabo mentions that in the territories united by Artashes I, “everyone is monolingual”, that is, all the inhabitants speak Armenian. Let us also note, Artashes I was one of the representatives of the Council of Elders of Eastern Armenia. He began his military operations against Yervand IV in Utik, and he was helped by the ministers of Uteatsots as well as the troops there (M. Khorenatsi, book II, ch. 44). A point of view put forward by the researchers H. Brown and G. Klimov in 1954, and again by I. Diakonoff in 1978 (I. Diakonoff, The Ancient East, Yerevan, 1978, [Collection]; Article: Hurrian-Urartian and East Caucasian Languages), should also be noted. According to this view, the languages of the East Caucasian tribes are connected with the languages of the Hurri-Mitannians and Ararat-Urartians. Note that those names are the ancient names used in Sumerian, Akkadian, Egyptian, Hittite, and other ancient cuneiform written sources for Hay-Armens, the natives of the Armenian Highlands. However, this view is not widely accepted among researchers. On the basis of these views and assumptions put forward and presented to them, the Azeri researchers include Artsakh and Gardman-Utik in the borders of their imagined state of Albania, and even speak about including Lake Sevan and Syunik. Meanwhile, the study of the works of Armenian historians, as well as the created political situation (the first and second divisions of Armenia, the need to fight against the repeated invasions of Caucasian mountaineers and other nomadic tribes) allows us to say that the works of historians present the Armenian peripheral state created in the territories separated from Hayk in the 4th century (after A.D. 387), as the kingdom of Aghvank (after 510 or 523, it was a marzban), which had an Armenian population and Christian faith, and was closely related to Armenia in spiritual, cultural, economic, and other aspects. Its leaders, kings, and catholicoi were connected to Armenia, Armenian kings, and Armenian catholicoi; constantly consulting with them, maintaining strong friendly ties, and often allying together in the fight against the Caucasian highlanders, various nomadic tribes that regularly appeared, and the Persian court.

The testimonies about the above-mentioned tribes made by Greek and Roman historians, refer to the Caucasian tribes living in the branches of the Caucasus Mountains, in the mountains and canyons. We notice that there is no central ethnic group, language, territory, or culture. These tribes spoke different languages and were at different levels of development. At best, they could band together to fight some external threat, in this case Roman invasions (as in the cases of Orois or Zober), or to organize marauding, predatory raids, the evidence of which is plentiful. Therefore, relying on information curated by Greek and Roman authors and saying that in the middle of the 1st century B.C., in the territory of the Left Bank Kur River, the state of Albania was formed from a union of tribes speaking 26 different languages, is a far-fetched assumption that is not supported by facts and evidence. Until the A.D. 4th century, in Greco-Roman written sources, there is only fragmentary information about Caspian-Kazbers, Albanians, and other tribes, related to Roman-Parthian wars, Armenian-Roman and Armenian-Parthian relations. We get additional information about Aghvank mainly through Armenian historians (Movses Khorenatsi, Pavstos Buzand, Ghazar Parpetsi, Movses Koghankatvatsi, Ashkharatsuyts) and Armenian written sources, which testify that in the north-eastern part of the Left Bank Kur in the Near Caspian region, at the beginning of the 4th century, the kingdom of the Maskut was formed under the leadership of the Parthian Arshakunis. Furthermore, Armenian historians attest to the the kingdom of Aghvank, its Armenian Aranshahik kings, the later marzpan formation of Aghvank (510), and other issues. The kingdom of the Maskut is presented by many researchers as the kingdom of Aghvank, which is incorrect because the Maskut tribe spoke an Iranian dialect and lived in the area between the Caspian Sea and Caucasus Mountains.

The majority of the tribes mentioned above by Greek, Roman, and Armenian historians, the Aghuatakans (now Akhti), Gheker (now Tsakurs), Tavaspars (now Tabasarantsis), Leker (now Lezgis), Lpnis (now Lahich), Didoy (Didoeti), and others, converted to Islam during Arab occupation and still live in their original places of residence in the areas between the southern spurs of the Caucasus Mountains and the Caspian Sea, in Dagestan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Again, let us note, those Caucasian tribes are connected to the kingdom of Aghvank that was formed in the Armenian-inhabited areas of Eastern Armenia, on the right and left banks of the Kur River, to protect Armenia, Persia, and other areas of the Caucasus from the attacks of the Caucasus mountaineers and nomadic tribes (under the patronage of Persia and Byzantium, Aghvank was assigned the role of a buffer state). In the year 510 (523), after the dissolution of the kingdom of Aghvan, Persian marzpans began to rule the country. In order to strengthen the Aghvank marzban formation, a number of territories of the Left Bank Kur were joined to it: Bazkan, Khoruan, Shruan, Choghan, as well as the Ghekats and Tavaspar provinces and the city of Darband (Derbend) with its fortifications. This was the largest territorial inclusion of Aghvank province (according to Ashkharatsuyts, an area of 72,204 km2, Aghvank is presented with these boundaries in table 42 of Trever’s aforementioned book).

There are various explanations about the origin of the names Albania and Aghvank. As mentioned above, Khorenatsi associated the name Aghvank with the “agu” (“sweet”) character of Sisak, a descendant of the Armenian patriarch Hayk, from whom the name of the region Aghvank arose. The name Aghvank mentioned in Armenian written sources, and the name Albania mentioned in Greco-Roman written sources do not seem to be alike at first glance, but more careful scrutiny reveals their similarities. We know that when foreigners are unable to pronounce a given name, they use a phonetic substitution to better suit it to their specific language. We can assume that in this instance, the Armenian name Aghvank (Alvank) was phonetically altered by Greeks and Romans into the form Albania, to suit their languages (gh-l and v-b phonetic changes were implemented).

Apart from the names Albania and Aghvank, the names Bun Aghvank, Caucasian Aghvank, and Armenian Aghvank were also used for this territory of Eastern Armenian. This variety (or jumble) of names occurred in the marzban period (after 510), after the first (387) and second (591) divisions of Armenia, when, as mentioned above, provinces inhabited by Caucasian tribes (Tavaspark, Maskut, Shogha, Gheck, Darband) were added to the Armenian-populated Aghvank, which was separated from Armenia and passed to Persia. The presence of the Udis and Gargars in Aghvank suggests that they (a part of the tribe) came down from their original places of residence, the Caucasus Mountains (Gargars) and the area between the Caspian Sea and the coastal mountains (Udis), to the fertile plain of the Kur River inhabited by Armenians (it is assumed that they were harassed by the Alans), where Mesrop Mashtots created a script for the Gargars in the 5th century. There is a viewpoint (A. Hakobyan) that the name Gargar is an arbitrary name, which was bestowed upon the wild northern tribes which appeared on the Left Bank Kur by Movses Khorenatsi (A. Hakobyan, Albania-Aluank in Greek-Latin and Ancient Armenian Sources, Yerevan, 1987, pp. 72-74). And the Udis, having found themselves in the Armenian environment, accepted Christianity, then shared the fate of Armenians: they forcibly became Muslims, migrated, or perished (in the Soviet years, a small group of them lived in the villages of Nizh and Vardashen of the Nukhi [now Shaki] region).

Thus, it is appropriate to claim that Aghvank (Albania) is the name of a territory, a region (Right Bank Kur, Left Bank Kur, Gardman, Utik, Artsakh), and not an ethnonym. Its inhabitants are Armenians, who did not, and do not, call themselves anything else (including my grandfathers and distant ancestors).

Gardman, which was annexed to Azerbaijan during the Soviet years, was divided into several regions: Dashkesan, Khanlar, Ghazakh, Shamkhor, Getabek, Touz, Kasum-Ismailov (Gyorani), and Shahumyan.

The desire of all the administrators of Soviet Azerbaijan was the same: create a homogeneous Turkish state. However, this proved difficult to implement in the case of Armenians, who had lived and continued to live in the land of their ancestors for thousands of years, had created a great culture, and were connected with Armenia by strong spiritual ties. That is the reason the government of Azerbaijan conducted an anti-Armenian policy from the very outset of its creation. Using economic, cultural, and educational issues, as well as violence and blackmail, the leaders of Azerbaijan pursued a policy of forcing Armenians out of their ancestral homeland. With emphatic slogans, they declare their country the most international country of the USSR, where representatives of different nations live in solidarity: Russians, Armenians, Jews, Ukrainians, Dagestanis, and representatives of other peoples. Unfortunately, not meeting serious opposition from the governments of Soviet Armenia and the USSR, the government of Azerbaijan managed to implement its plans. The history of the beginning of the century was repeated in 1988-1990, when in order to save the communist regime, with the permission of the Soviet authorities, anti-Armenian pogroms were organized in Sumgait, Baku, Gandzak, and other places.

The Gardman Armenians, who waited with great hope for the Christian Russians from the 18th century, linked the success of their liberation struggle with the Russians’ arrival. However, after nearly 200 years, the Gardman Armenians, who had done so much to strengthen the success of Russian weapons in Transcaucasia, were pushed out of their cradle and scattered into the world between 1988-1992, with the help of the same Russian military forces. Taking advantage of its autonomous status, Artsakh was able to win the war imposed upon it, and was liberated from Turkish rule. However, the victory is not final, as most of the Armenian Aghvan lands, including Gardman, are still in captivity, as are other Armenian lands. A proud and heroic citizen of Gardman cannot come to terms with the reality that exists there today. We believe that the day will come when Armenian carpets will again be woven in the world of Gardman, temples and khachkars will be built, and Armenian archaeologists will excavate settlements and proudly present to the world the high culture and civilization created by their ancestors.

ANGELA A. TERYAN, HISTORIAN

TRANSLATED BY ANNA GAGIKI MATSOYAN HODNETT